|

| Photo: Shayne Kaye/Flickr/Public Domain |

Friday, April 29, 2016

Tree on Log

In British Columbia. I read that the larger tree is a "nurse log."

Via Slate.

Dangerous Wet Bulb Temperatures in India

It's not even May yet, but at least one city in India has reached dangerous wet bulb temperatures.

A WBT of 30-35°C is dangerous. If you're engaged in physical activity, 27°C or above can be dangerous. 33°C is dangerous even for if you're naked and lying in the shade. Wikipedia says 35°C. At that temperature you literally cannot cool off (without A/C) -- perspiration can't evaporate fast enough; you start to be cooked. Not good if you're poor or don't have electricity (300 M people do not), or you can't afford an A/C.

I used recent data from Wunderground for Titlagarh, India, in southeastern India, which I read was having a heat wave. (People cannot go out in the street during the day; social events have to take place in the evenings. 99 deaths so far.) On April 24th, their high temperature was 119°F (48.3°C), and their wet bulb temperature reached about 32.4°C. On April 26th it was 113 F° (45.0°C) but more humid, with a WBT of 32.8°C.

And it's only April.

N.b. You really need to know temperature, relative humidity and surface pressure as functions of time; the weather site only gives daily highs, daily lows, and daily aveages. In the above I used the high relative humidities for the day, and the high surface pressure.

With the high temperaure and average RH and average pressure, the numbers are 29,2°C and 31.4°C respectively -- still dangerous.

A WBT of 30-35°C is dangerous. If you're engaged in physical activity, 27°C or above can be dangerous. 33°C is dangerous even for if you're naked and lying in the shade. Wikipedia says 35°C. At that temperature you literally cannot cool off (without A/C) -- perspiration can't evaporate fast enough; you start to be cooked. Not good if you're poor or don't have electricity (300 M people do not), or you can't afford an A/C.

A sustained wet-bulb temperature exceeding 35 °C (95 °F) is likely to be fatal even to fit and healthy people, unclothed in the shade next to a fan; at this temperature our bodies switch from shedding heat to the environment, to gaining heat from it.[7] Thus 35 °C is the threshold beyond which the body is no longer able to adequately cool itself.Given the temperature, humidity and surface pressure, this NOAA site returns the WBT. I wrote about WBTs for last year's heat wave in the Persian Gulf here.

I used recent data from Wunderground for Titlagarh, India, in southeastern India, which I read was having a heat wave. (People cannot go out in the street during the day; social events have to take place in the evenings. 99 deaths so far.) On April 24th, their high temperature was 119°F (48.3°C), and their wet bulb temperature reached about 32.4°C. On April 26th it was 113 F° (45.0°C) but more humid, with a WBT of 32.8°C.

And it's only April.

N.b. You really need to know temperature, relative humidity and surface pressure as functions of time; the weather site only gives daily highs, daily lows, and daily aveages. In the above I used the high relative humidities for the day, and the high surface pressure.

With the high temperaure and average RH and average pressure, the numbers are 29,2°C and 31.4°C respectively -- still dangerous.

Thursday, April 28, 2016

What is the Trend in the Airborne Fraction of CO2?

In the wake of the recent CO2 fertilization/greening world paper (I think this is good coverage of what it means, which is not "hallelujah"), And Then There's Physics wrote a post about the airborne fraction (AF) of CO2 -- what fraction of the CO2 we emit stays in the atmosphere? Because as we continue to emit CO2, its AF is by no means guaranteed to stay what it is now, and no one seems to really know how it will change. The concern, of course, is that it increases as nature becomes closer to saturation (the Amazon is already taking up less CO2) and as the ocean continues to warm.

ATTP gave a result by Pierre Friedlingstein that gives a result based on RCP, since 1990:

You can read his discussion.

There are surely studies around that discuss this. But I thought I might have enough spreadsheets laying around to perhaps estimate down-and-dirty the actual trend in airborne fraction.

Here are my data:

ATTP gave a result by Pierre Friedlingstein that gives a result based on RCP, since 1990:

You can read his discussion.

There are surely studies around that discuss this. But I thought I might have enough spreadsheets laying around to perhaps estimate down-and-dirty the actual trend in airborne fraction.

Here are my data:

- the atmospheric CO2 fraction since 1959 (the Keeling Curve), where for each year I took the average of 12 months from the monthly Mauna Lea data, from which one can compute the mass of CO2 in the atmosphere, 1959-2015.

- World CO2 emissions from combustion, cement production and gas flaring from CDIAC, 1751-2005.

- World CO2 emissions from land use changes from CDIAC, 1850-2005.

- I assumed atmospheric CO2 for 1850 was 280 ppm.

Here are the trends I find (click to enlarge):

There's considerable annual variation (blue points), but basically the 10-year moving average for AF is flat. So is the total AF since 1850. The last 10 years look like the annual AF has less variation, but that's also where my input data is the less certain (see note below).

N.b. Someone doing this right would need good data all the way to 2015, or up to the last year that is available. One problem in my data are the last two datasets stop in 2005. As an attempt to extend them, I used these data for combustion+cement+flaring for 2006-2008. Beyond 2008 I used IEA data for fossil fuel emissions; for land use emissions I assumed 400 Mt C/yr from 2006-2015, slightly bigger than the last few numbers here up to 2005 (Chinese growth), and flaring emissions of 1.3 Mt C/yr, the value for 2008 (it's a small amount anyway). And I assumed land use emissions per year for 2007-2015 were the average of the previous 10 years, which is 1,479 Mt C/yr. I ignored methane emissions, which converts to CO2 after several years. (I said, down-and-dirty.)

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

A Batch of Interesting Papers

There are a bunch of especially interesting papers in tonight's table of contents from Geophysical Research Letters. I haven't read any of them yet, but am posting them because (1) some pertain to things being discussed back on this post, (2) you can read yourself if so motivated.

I'll post the paper's citation, a link to it, and the three-bullet summary of the paper from the table of contents:

"Predictability of the recent slowdown and subsequent recovery of large-scale surface warming using statistical methods," Michael E. Mann et al, GRL (8 April 2016).

"Emergence of heat extremes attributable to anthropogenic influences," Andrew D. King et al, GRL (2 April 2016).

"Nonlinearities in patterns of long-term ocean warming," Maria A. A. Rugenstein et al, GRL (4 April 2016).

"The impact of groundwater depletion on spatial variations in sea level change during the past century," Emeline Veit et al, GRL (2 April 2016).

"Ice mass loss in Greenland, the Gulf of Alaska, and the Canadian Archipelago: Seasonal cycles and decadal trends," Christopher Harig et al, GRL (5 April 2016).

I'll post the paper's citation, a link to it, and the three-bullet summary of the paper from the table of contents:

"Predictability of the recent slowdown and subsequent recovery of large-scale surface warming using statistical methods," Michael E. Mann et al, GRL (8 April 2016).

"Emergence of heat extremes attributable to anthropogenic influences," Andrew D. King et al, GRL (2 April 2016).

"Nonlinearities in patterns of long-term ocean warming," Maria A. A. Rugenstein et al, GRL (4 April 2016).

"The impact of groundwater depletion on spatial variations in sea level change during the past century," Emeline Veit et al, GRL (2 April 2016).

"Ice mass loss in Greenland, the Gulf of Alaska, and the Canadian Archipelago: Seasonal cycles and decadal trends," Christopher Harig et al, GRL (5 April 2016).

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Sloooooooooow Progress on Renewables

I assembled this for something I'm working on:

Here renewable energy = hydro + geothermal + solar/PV + wind + biomass

Although renewables have increased by about 4 percentage points in 8 years, which is -0.5 pct pts/year. Not fast enough. Drew Shindell says we need a decrease in fossil fuel emissions of something like 2.7%/yr.

I also came up with this:

Data from EIA.

Here renewable energy = hydro + geothermal + solar/PV + wind + biomass

Although renewables have increased by about 4 percentage points in 8 years, which is -0.5 pct pts/year. Not fast enough. Drew Shindell says we need a decrease in fossil fuel emissions of something like 2.7%/yr.

I also came up with this:

Data from EIA.

Monday, April 25, 2016

Is Abdussamatov's Prediction of a TSI Collapse Coming True?

Remember that dip in total solar irradiance (TSI) that had some people excited last week?

It's gone. It was just a sunpot:

However, TSI is doing something interesting: it's dropping relatively fast now, down about 1 W/m2 since its peak in early 2015.

LASP's daily record only starts in early 2003. PMOD starts in 1978, and, except for the lower solar maximum for this latest cycle, it doesn't appear anything particularly unusual is going on:

It will be interesting to see the current cycle's minimum, but that won't be for another 5-6 years. Will it match this Internet-famous prediction from Abdussamatov in his paper that finally seems to have gotten published in a journal titled Thermal Science:

Is his prediction coming true?

Here's a plot showing about where he says TSI should be in 2016:

Abdussamatov says TSI should now be about 0.7 W/m2 below the baseline of the cycles from 1980-2010. The PMOD data certainly doesn't show that -- it's still above that baseline, by about 0.3 W/m2. Abdussamatov is too low by a whole W/m2, which is a significant amount when you're talking about the sun.

So I would say that, so far, Abdussamatov's prediction is failing, and there's no indication of the TSI collapse he predicted. We have not entered his Little Ice Age.

It's gone. It was just a sunpot:

However, TSI is doing something interesting: it's dropping relatively fast now, down about 1 W/m2 since its peak in early 2015.

LASP's daily record only starts in early 2003. PMOD starts in 1978, and, except for the lower solar maximum for this latest cycle, it doesn't appear anything particularly unusual is going on:

It will be interesting to see the current cycle's minimum, but that won't be for another 5-6 years. Will it match this Internet-famous prediction from Abdussamatov in his paper that finally seems to have gotten published in a journal titled Thermal Science:

Is his prediction coming true?

Here's a plot showing about where he says TSI should be in 2016:

So I would say that, so far, Abdussamatov's prediction is failing, and there's no indication of the TSI collapse he predicted. We have not entered his Little Ice Age.

Friday, April 22, 2016

Thursday, April 21, 2016

The Shock of Seeing Anomalies Above 2°C

This month's data -- temperatures, global, land and sea; lower troposphere up to lower stratosphere, sea ice extent and volume, Mauna Loa CO2 and all the ocean indices -- are now out, except for HadCRUT4 and, then, Cowtan & Way. They're always about two weeks later than GISS and NOAA.

To me, the most astonishing numbers are from NOAA's measurement of the average global land temperature, averaged across the globe's surface. The last two months have been well above 2°C:

I've been paying close attention to all these monthly data for many years now, and seeing anomalies -- any anomaly -- approaching +2.5°C is really shocking, in quite an other worldly kind of way. (The anomaly is with respect to the 1901-2000 average*.)

NOAA's global land anomaly for March 1998 is only +0.88°C. This March it is +2.33°C.

That's a lot of warming in 18 years, from one big El Nino to the next one.

I don't know if the 2°C diplomatic target means 2°C for the change in the global surface average, or for a change anywhere -- and since the number is, as far as I know, just a guess at a target that is both doable and not too dangerous, I doubt anyone even thought to think that question much....

Americans: an anomaly of 2.33°C = 4.2°F. That is perceptable without instruments.

The warming has been coming at a steady 0.15-0.2°C/decade since 1990. So when I see stories saying that 93% of the Great Barrier Reef has died because of exceptionally warm ocean water, I start to feel angry about that. Deeply angry -- at everyone who is denying serious anthropogenic climate change and who is working hard to prevent us from saving the world that we know and love. And angry at those I personally know who are denying it.

And I don't just mean angry in a scientific way. The Great Barrier Reef was one of the marvels of the Universe. If you don't care about marvels of the Universe, then what in the hell do you care about?

--

* And can I say, is it really too much to ask that all the different research groups use the same baseline? Yes, I know that converting between them is doable and mathematically trivial. But's it's also tedious. And, yes, I know that trends are independent of baselines. But still....

To me, the most astonishing numbers are from NOAA's measurement of the average global land temperature, averaged across the globe's surface. The last two months have been well above 2°C:

I've been paying close attention to all these monthly data for many years now, and seeing anomalies -- any anomaly -- approaching +2.5°C is really shocking, in quite an other worldly kind of way. (The anomaly is with respect to the 1901-2000 average*.)

NOAA's global land anomaly for March 1998 is only +0.88°C. This March it is +2.33°C.

That's a lot of warming in 18 years, from one big El Nino to the next one.

I don't know if the 2°C diplomatic target means 2°C for the change in the global surface average, or for a change anywhere -- and since the number is, as far as I know, just a guess at a target that is both doable and not too dangerous, I doubt anyone even thought to think that question much....

Americans: an anomaly of 2.33°C = 4.2°F. That is perceptable without instruments.

The warming has been coming at a steady 0.15-0.2°C/decade since 1990. So when I see stories saying that 93% of the Great Barrier Reef has died because of exceptionally warm ocean water, I start to feel angry about that. Deeply angry -- at everyone who is denying serious anthropogenic climate change and who is working hard to prevent us from saving the world that we know and love. And angry at those I personally know who are denying it.

And I don't just mean angry in a scientific way. The Great Barrier Reef was one of the marvels of the Universe. If you don't care about marvels of the Universe, then what in the hell do you care about?

--

* And can I say, is it really too much to ask that all the different research groups use the same baseline? Yes, I know that converting between them is doable and mathematically trivial. But's it's also tedious. And, yes, I know that trends are independent of baselines. But still....

Wednesday, April 20, 2016

"Boaty McBoatface" is Going to Be a Huge Missed Opportunity

| A mock-up of the future research vessel |

But I think they are missing a great opportunity.

This ship has already gotten far more exposure than they could have ever bought.

Sure, it's a little silly. But it's joyfully silly, not perjoratively silly.

Give it some "dignified" (quote-unquote) name -- say, the RSS David Attenborough -- and watch the boat's activites be overlooked and forgotten as it blends into the background of the world. But name it "Boaty McBoatface" and they'll get coverage from the newspaper of every city's port they pull in to.

People will recognize it for a long time. They'll remember the naming process and will be interested to see what the boat is up to when they encounter it again. Or they'll wonder why the boat has such an unusual name and read the article about it. In an often dreary world, they'll smile to themselves when the article concludes.

The captain will get interviews he wouldn't have otherwise received. The crew will smile for the cameras, happy to be on a ship of note. Sailors will know about it the world over. Every journalist will click on the press releases with the name in the headline.

This name is a gift. I know the British, and especially its officials, have a reputation for being staid, but I hope they take the gift they have been given. I don't see it detracting from their mission at all.

More About Improved U.S. Weather Conditions from Global Warming

More about the Egan and Mullin paper discussed here, concluding "in the United States from 1974 to 2013, the weather conditions

experienced by the vast majority of the population improved."

On a closer inspection, my skepticism is growing.

As I said, the paper looked at where people moved, and found that, on avarage, they perferred warmer temperatures and less humid summers. Their study gives, for each year, a data point that represents the populated-weighted preferred value for temperature, humidity, precipitation, and days of precipition -- these are the figures to the right. (Click to enlarge.)

As I said, the paper looked at where people moved, and found that, on avarage, they perferred warmer temperatures and less humid summers. Their study gives, for each year, a data point that represents the populated-weighted preferred value for temperature, humidity, precipitation, and days of precipition -- these are the figures to the right. (Click to enlarge.)

The thick black lines are calculated by LOWESS regression.

But much of this data is quite scattered --only graph b, for mean daily maximum tempertures in July, is tight enough for a fitted curve to be obvious.

I'm not an expert in Loess regression, but my reaction here is to be very skeptical about trying to extract meaningful curves from such widely scattered data -- curves meaningful enough that useful information can be found in their trends.

I'm not an expert in Loess regression, but my reaction here is to be very skeptical about trying to extract meaningful curves from such widely scattered data -- curves meaningful enough that useful information can be found in their trends.

Consider graph c, plotting mean daily relative humidity for July. Why did people (population-weighted people) perfer higher humidities from 1974 to about 1995, and then preferred lower humidities from 1995 to 2013?

Or graph a: why did people cease to care about the mean daily maximum temperature in January after about 1993? Or at least care enough to move on account of it?

It seems to me that too much else is going on with people's decisions to move than simply a preference for a climate. I've lived in 10 different states, and most of the time I moved it wasn't for climate, it was for opportunity. (Except that I did choose to go to graduate school back east, partly for the climate, and I moved from Arizona and to New England in fair part because of climate. But I moved to Arizona for an opportunity, and I left New England and came to Oregon for an opportunity, not for climate or weather. Frankly I miss New England's weather (except in April and May.))

So where did people -- again, population-weighted people -- move from, and where did they move to? From the paper:

The results on the map aren't especially surprising. But, again, to assume people move purely for weather is simplistic. The population of the U.S. has, on average, been aging over recent decades. Older people might tend to favor warmer temperatures on average, but until recent decades many didn't have the money to move to a more favorable climate after retiring. The rust belt in the US -- Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, etc -- has lost jobs due to global economic forces, and people had to move to where they could find new jobs. Living in the northeastern US is relatively expensive, so naturally people look away from that region when they considered moving. Colorado might have better weather, in the eyes of many, than Massachusetts, but it defintely had lower home prices. And then there's culture. Utah might have great weather, but its culture is one that not everyone would prefer moving to.

And so on.

On a closer inspection, my skepticism is growing.

As I said, the paper looked at where people moved, and found that, on avarage, they perferred warmer temperatures and less humid summers. Their study gives, for each year, a data point that represents the populated-weighted preferred value for temperature, humidity, precipitation, and days of precipition -- these are the figures to the right. (Click to enlarge.)

As I said, the paper looked at where people moved, and found that, on avarage, they perferred warmer temperatures and less humid summers. Their study gives, for each year, a data point that represents the populated-weighted preferred value for temperature, humidity, precipitation, and days of precipition -- these are the figures to the right. (Click to enlarge.)The thick black lines are calculated by LOWESS regression.

But much of this data is quite scattered --only graph b, for mean daily maximum tempertures in July, is tight enough for a fitted curve to be obvious.

I'm not an expert in Loess regression, but my reaction here is to be very skeptical about trying to extract meaningful curves from such widely scattered data -- curves meaningful enough that useful information can be found in their trends.

I'm not an expert in Loess regression, but my reaction here is to be very skeptical about trying to extract meaningful curves from such widely scattered data -- curves meaningful enough that useful information can be found in their trends.Consider graph c, plotting mean daily relative humidity for July. Why did people (population-weighted people) perfer higher humidities from 1974 to about 1995, and then preferred lower humidities from 1995 to 2013?

Or graph a: why did people cease to care about the mean daily maximum temperature in January after about 1993? Or at least care enough to move on account of it?

It seems to me that too much else is going on with people's decisions to move than simply a preference for a climate. I've lived in 10 different states, and most of the time I moved it wasn't for climate, it was for opportunity. (Except that I did choose to go to graduate school back east, partly for the climate, and I moved from Arizona and to New England in fair part because of climate. But I moved to Arizona for an opportunity, and I left New England and came to Oregon for an opportunity, not for climate or weather. Frankly I miss New England's weather (except in April and May.))

So where did people -- again, population-weighted people -- move from, and where did they move to? From the paper:

The value plotted is their mean WPI -- weather preference index -- by county. They write that WPI is "an indicator of the average American’s revealed preference for different types of weather conditions. The WPI’s unit of measure is the ceteris paribus expected rate of population change associated with that year’s weather."

They add, "In using these studies for our purposes, we assume that, all things being equal, Americans move to, and continue to reside in, places with local climates that they prefer."

The results on the map aren't especially surprising. But, again, to assume people move purely for weather is simplistic. The population of the U.S. has, on average, been aging over recent decades. Older people might tend to favor warmer temperatures on average, but until recent decades many didn't have the money to move to a more favorable climate after retiring. The rust belt in the US -- Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, etc -- has lost jobs due to global economic forces, and people had to move to where they could find new jobs. Living in the northeastern US is relatively expensive, so naturally people look away from that region when they considered moving. Colorado might have better weather, in the eyes of many, than Massachusetts, but it defintely had lower home prices. And then there's culture. Utah might have great weather, but its culture is one that not everyone would prefer moving to.

And so on.

This Paper Will Cause a Lot of Problems....

Nature just published a paper that isn't very surprising, but will be at least a little confusing to those who are concerned about anthropogenic global warming, and immediately and loudly exploited by "skeptics." I suspect it is going to be difficult for those concerned about AGW to counter.

"Recent improvement and projected worsening of weather in the United States," Patrick J. Egan & Megan Mullin, Nature (2016).

+0.07 °C per decade.

However, people often move for reasons other than weather -- notably for economic reasons, and this may be a weak point of this study: the decline in rust belt jobs and the expansion in jobs in warmer parts of the country, notably the southwest. But you could counterargue that the jobs are in "better" climates because that's where people are moving.

In any case, a little better weather -- or, at least, the perception of better weather -- comes with a problem: we can't naturally (viz. without geoengineering) stop global warming on a dime; nature's thermostat doesn't work that way. And therein lies the rub.

The abstract continues:

But the optics (as they say) of this paper are bad.

Obviously the counterpoints to it are:

And it will be intertesting to see how this study is covered by the media.

Added: More thoughts, and more skepticism, at my next post.

"Recent improvement and projected worsening of weather in the United States," Patrick J. Egan & Megan Mullin, Nature (2016).

Here we show that in the United States from 1974 to 2013, the weather conditions experienced by the vast majority of the population improved. Using previous research on how weather affects local population growth to develop an index of people’s weather preferences, we find that 80% of Americans live in counties that are experiencing more pleasant weather than they did four decades ago. Virtually all Americans are now experiencing the much milder winters that they typically prefer, and these mild winters have not been offset by markedly more uncomfortable summers or other negative changes.Basically this study looked at where Americans moved over this time period. This isn't a perfect proxy for weather preference, but the authors write "all published population growth models reveal the same preference structure with respect to seasonal temperatures: Americans appreciate warm winters and dislike hot, humid summers." By looking at changes in county populations (and excluding Alaska), the authors found that on average the population shifted towards a climate with a change in daily maximum January temperatures of +0.58 °C per decade, and daily maximum July temperatures rose by only

+0.07 °C per decade.

However, people often move for reasons other than weather -- notably for economic reasons, and this may be a weak point of this study: the decline in rust belt jobs and the expansion in jobs in warmer parts of the country, notably the southwest. But you could counterargue that the jobs are in "better" climates because that's where people are moving.

In any case, a little better weather -- or, at least, the perception of better weather -- comes with a problem: we can't naturally (viz. without geoengineering) stop global warming on a dime; nature's thermostat doesn't work that way. And therein lies the rub.

The abstract continues:

Climate change models predict that this trend is temporary, however, because US summers will eventually warm more than winters. Under a scenario in which greenhouse gas emissions proceed at an unabated rate (Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5), we estimate that 88% of the US public will experience weather at the end of the century that is less preferable than weather in the recent past. Our results have implications for the public’s understanding of the climate change problem, which is shaped in part by experiences with local weather. Whereas weather patterns in recent decades have served as a poor source of motivation for Americans to demand a policy response to climate change, public concern may rise once people’s everyday experiences of climate change effects start to become less pleasant.Many people will understand that global warming doesn't stop here, but they might wonder if this result should make them do a little rethinking. But many people won't understand this on purpose, and use this to study for the cause of denial.

But the optics (as they say) of this paper are bad.

Obviously the counterpoints to it are:

- The US isn't the world, and just because weather has gotten better here doesn't mean it's gotten better elsewhere or everywhere.

- Sea level is still rising, ice is still melting, and the ocean is still acidifying. There is far more to global warming than the weather or temperature you experience.

- The warming is already having consequences this study doesn't capture. It's making droughts worse. (Whether it had a hand in creating a drought nor not, global warming always makes droughts worse because it increase evaporation rates.) Extreme rainfall events are increasing.

- Just you wait.

And it will be intertesting to see how this study is covered by the media.

Added: More thoughts, and more skepticism, at my next post.

Tuesday, April 19, 2016

Why the Sun's Irradiance Recently Dipped

See this post for background.... The 0.7 W/m2 dip or so was from this sunspot, Greg Kopp of LASP tells me: "This is the Sun about a week ago when that dip occurred. Nothing to write home about. That people are excited about this may reflect that the current solar cycle has not been one of the most exciting ones."

So the global cooling apocalypse can be put off for another day....

PS: Eli also got this.

So the global cooling apocalypse can be put off for another day....

PS: Eli also got this.

No, the Sun Isn't in Long-term Rapid Cooling

The WUWT crowd are excited because of this graph:

The Sun is rapidly cooling! So global warming will start reversing any day now, and by 2020 we'll be back to zero anomalies and this AGW crap can be put to bed and the legal prosecutions of scientists can begin. (Or something like that, I guess.)

Sorry, but the Sun goes through dips and spikes like this several times a year, typically (though I don't know the reason.) Here is a graph of the same data as above, but starting in Jan 2014 instead of Jan 2016:

By starting the graph in Jan 2016, WUWT makes it look like the first spike of the year is something unusual. But it's just business as usual.... (I commented on this at WUWT, but -- cowards -- they deleted my comment.)

--

Reminder: anyway, the climate's sensitivity to changes in solar irradiance is very low, ≈ 0.1 W/m2 or less.

PS: Leif Svalgaard of Stanford says these spikes are due to large sunspots.

The Sun is rapidly cooling! So global warming will start reversing any day now, and by 2020 we'll be back to zero anomalies and this AGW crap can be put to bed and the legal prosecutions of scientists can begin. (Or something like that, I guess.)

Sorry, but the Sun goes through dips and spikes like this several times a year, typically (though I don't know the reason.) Here is a graph of the same data as above, but starting in Jan 2014 instead of Jan 2016:

By starting the graph in Jan 2016, WUWT makes it look like the first spike of the year is something unusual. But it's just business as usual.... (I commented on this at WUWT, but -- cowards -- they deleted my comment.)

--

Reminder: anyway, the climate's sensitivity to changes in solar irradiance is very low, ≈ 0.1 W/m2 or less.

PS: Leif Svalgaard of Stanford says these spikes are due to large sunspots.

Monday, April 18, 2016

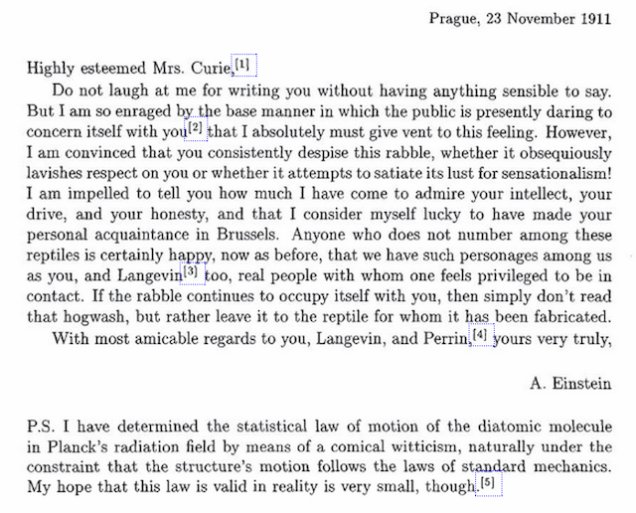

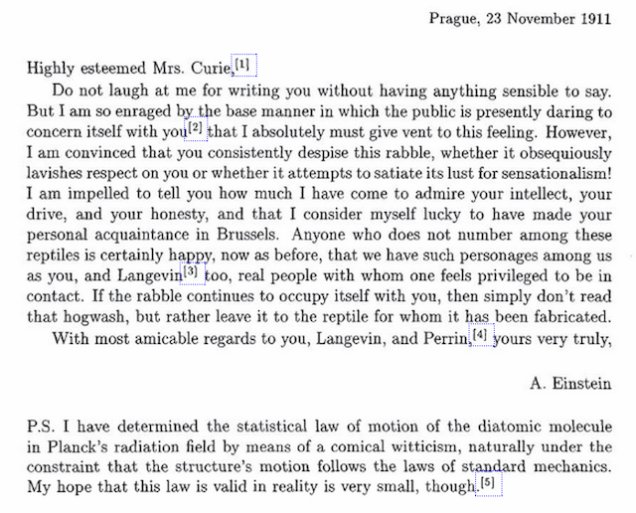

Einstein's Climategate

Imagine if this letter from Albert Einstein to Marie Curie had been stolen by thieves and dropped into today's public domain.

The disrespect! The manufactured controversy! Einstein calls the uninformed of the time "reptiles." Morano would bold print that and paste up Einstein's email address in red! Imagine the scandal this letter would create today, if it came in a Climategate-like email. First Einstein calls the deniers "rabble." Then he calls their views "hogwash." And just look at the grand collusion between these two elitists, one washing the back of the other, profuse praise, ignoring the collective wisdom of the hoi polloi in favor of their made-up physics. What hautiness! What arrogance! Watch Joe Barton and Lamar Smith summon up a Congressional hearing! Won't someone audit their scientific claims -- it's the least they can do! (The very least.)

The disrespect! The manufactured controversy! Einstein calls the uninformed of the time "reptiles." Morano would bold print that and paste up Einstein's email address in red! Imagine the scandal this letter would create today, if it came in a Climategate-like email. First Einstein calls the deniers "rabble." Then he calls their views "hogwash." And just look at the grand collusion between these two elitists, one washing the back of the other, profuse praise, ignoring the collective wisdom of the hoi polloi in favor of their made-up physics. What hautiness! What arrogance! Watch Joe Barton and Lamar Smith summon up a Congressional hearing! Won't someone audit their scientific claims -- it's the least they can do! (The very least.)

Sunday, April 17, 2016

Hilarious Statement Tries to Dismiss Consensus

Judith Curry just highlighted something from somebodies on some blog which (naturally) she agree with:

By there logic, there is absolutely no evidence whatsoever for the existence of atoms or conservation of energy, because there's a universal consensus on both.

Look: scientists agree about a great deal in science -- yes, consensus is everywhere except at the edges where research is taking place -- and the sciences that are used to calculate global warming from the many possible physical sources is very well-established science. All scientists agree on the basic laws of quantum mechanics, including the Planck Law (its integral is the Stefan-Boltzmann law), and radiation physics, and the absorption/emission spectrums of the greenhouse gases. As well as the thermodynamics and other physics that go into atmospheric dynamics, which again, are not that complicated and about which there is near-universal agreement.

Given all this, it's just a matter of analyzing and calculating. The consensus of the underlying sciences doesn't mean the calculations are easy -- they certainly aren't, especially for the particulars of the carbon cycle. (Not many deniers seem to realize that the radiative transfer parts of global warming science are among the best known parts of the subject, because they are the most amenable to the standard techniques of analytical physics that physicists have been doing for a long time and are very good at.) Calculating climate sensitivity, which decades of successively more thorough calculations find to be ≈ 3°C ± 1.5°C (note: the uncertainty here just represents the range, not the standard deviation or uncertainly limit), is probably the most difficult calculation scientists have ever attempted. The error bars are still bigger than anyone would like -- but it may not be able to reduce them much more -- but not nearly so big as to justifying ignoring the problem or, given the huge amounts of greenhouse gases we're emitting, waiting for more information while the world keeps warming about about 0.15-0.2°C/decade, which has been the 30-year trend for over a quarter of a century now.

But scientists certainly haven't ignored all other potential causes of modern warming besides anthropogenic GHGs -- indeed, they've looked at them very thoroughly. Because that's what scientists do and how they operate. It's simply that the the data on other possible causes (like changers in solar irradiance) simply do not show they can create as much warming as we're seeing, by a long shot.

And no scientist accepts AGW because there is a "consensus" about it. Again, that's not how the scientists in the field operate (though, knowing what consensus is and isn't, scientists in other fields, knowing how science operates, tend to accept as the consensus as what scientists in the field say it is).

The funny thing is, the absolute best way for any scientist today to get noticed, get tenure, and certainly become famous, would be to prove AGW is wrong. There's a good reason that doesn't happen -- AGW isn't wrong.

Meanwhile, the theory and data on the enhancing the greenhouse effect do show the warming expected from aGHGs, within uncertainties.

Whoever these Brumberg fellows are, they have a poor understanding of science, including the science of anthropogenic global warming. And their excuse is not just laughable, but desperate.

The warmer it gets, the more nuts are falling out of the trees.

There's only one reason it's talked about with regard to climate science, and that's because the issue is of such importance and too complicated for most of the public to fully understand.

Warming is proceeding so rapidly that societies need to make decisions about it now (and should have 20 years ago). These decisions are and will require changes in public policies, but how is the public supposed to know if the decisions are warranted? Since they're not going to learn quantum mechanics and radiative physics and the particulars of the carbon cycle, they need some other standard on which to base their reactions, and the only other thing that is available is the degree of agreement of scientists on the underlying cause(s) of global warming. And there is a consensus on that -- man's emissions of greenhouse gases from burning fossil fuels.

String theory need not involve the public, besides funding it. Or the search for the Higgs boson, or most of what the world's chemists, geologists, biologists, physicists and others are working on. But there are a few scientific topics that stand out as having important consequences at this point and time -- such as tobacco's health effects, ozone depletion, genetically modified organisms, CRISPR/Cas9, artificial intelligence -- and there "consensus" is about all nonspecialists have to go on if they are to form a judgement and what steps should be taken.

So attempts to gauge the degree of consensus are important (though personally I find them boring) and meaningful, and hence the recent Cook et al metastudy on it. But I don't see any more studies, such as metanstudies where n>1, are going to convince people who don't want to acknowledge the consensus in the first place for reasons that have nothing to do with science.

"In our view, the fact that so many scientists agree so closely about the [causes of the] earth’s warming is, itself, evidence of a lack of evidence for [human caused] global warming."This is a truly hilarious statement, that could only have been made by nonscientists. (I haven't been able to identify these Brumberg chaps, but I'd bet.) That any scientist, even Curry, would agree with it is quite puzzling.

– D. Ryan Brumberg and Matthew Brumberg

By there logic, there is absolutely no evidence whatsoever for the existence of atoms or conservation of energy, because there's a universal consensus on both.

Look: scientists agree about a great deal in science -- yes, consensus is everywhere except at the edges where research is taking place -- and the sciences that are used to calculate global warming from the many possible physical sources is very well-established science. All scientists agree on the basic laws of quantum mechanics, including the Planck Law (its integral is the Stefan-Boltzmann law), and radiation physics, and the absorption/emission spectrums of the greenhouse gases. As well as the thermodynamics and other physics that go into atmospheric dynamics, which again, are not that complicated and about which there is near-universal agreement.

Given all this, it's just a matter of analyzing and calculating. The consensus of the underlying sciences doesn't mean the calculations are easy -- they certainly aren't, especially for the particulars of the carbon cycle. (Not many deniers seem to realize that the radiative transfer parts of global warming science are among the best known parts of the subject, because they are the most amenable to the standard techniques of analytical physics that physicists have been doing for a long time and are very good at.) Calculating climate sensitivity, which decades of successively more thorough calculations find to be ≈ 3°C ± 1.5°C (note: the uncertainty here just represents the range, not the standard deviation or uncertainly limit), is probably the most difficult calculation scientists have ever attempted. The error bars are still bigger than anyone would like -- but it may not be able to reduce them much more -- but not nearly so big as to justifying ignoring the problem or, given the huge amounts of greenhouse gases we're emitting, waiting for more information while the world keeps warming about about 0.15-0.2°C/decade, which has been the 30-year trend for over a quarter of a century now.

But scientists certainly haven't ignored all other potential causes of modern warming besides anthropogenic GHGs -- indeed, they've looked at them very thoroughly. Because that's what scientists do and how they operate. It's simply that the the data on other possible causes (like changers in solar irradiance) simply do not show they can create as much warming as we're seeing, by a long shot.

And no scientist accepts AGW because there is a "consensus" about it. Again, that's not how the scientists in the field operate (though, knowing what consensus is and isn't, scientists in other fields, knowing how science operates, tend to accept as the consensus as what scientists in the field say it is).

The funny thing is, the absolute best way for any scientist today to get noticed, get tenure, and certainly become famous, would be to prove AGW is wrong. There's a good reason that doesn't happen -- AGW isn't wrong.

Meanwhile, the theory and data on the enhancing the greenhouse effect do show the warming expected from aGHGs, within uncertainties.

Whoever these Brumberg fellows are, they have a poor understanding of science, including the science of anthropogenic global warming. And their excuse is not just laughable, but desperate.

The warmer it gets, the more nuts are falling out of the trees.

--

So why even mention the consensus?There's only one reason it's talked about with regard to climate science, and that's because the issue is of such importance and too complicated for most of the public to fully understand.

Warming is proceeding so rapidly that societies need to make decisions about it now (and should have 20 years ago). These decisions are and will require changes in public policies, but how is the public supposed to know if the decisions are warranted? Since they're not going to learn quantum mechanics and radiative physics and the particulars of the carbon cycle, they need some other standard on which to base their reactions, and the only other thing that is available is the degree of agreement of scientists on the underlying cause(s) of global warming. And there is a consensus on that -- man's emissions of greenhouse gases from burning fossil fuels.

String theory need not involve the public, besides funding it. Or the search for the Higgs boson, or most of what the world's chemists, geologists, biologists, physicists and others are working on. But there are a few scientific topics that stand out as having important consequences at this point and time -- such as tobacco's health effects, ozone depletion, genetically modified organisms, CRISPR/Cas9, artificial intelligence -- and there "consensus" is about all nonspecialists have to go on if they are to form a judgement and what steps should be taken.

So attempts to gauge the degree of consensus are important (though personally I find them boring) and meaningful, and hence the recent Cook et al metastudy on it. But I don't see any more studies, such as metanstudies where n>1, are going to convince people who don't want to acknowledge the consensus in the first place for reasons that have nothing to do with science.

Thursday, April 07, 2016

Blankenship Goes to Jail

NYT:

"Mr. Blankenship was a hard-driving executive who demanded productivity reports every 30 minutes. He retired after the explosion with a $12 million golden parachute. “This game is about money,” he was heard emphasizing in one recorded comment uncovered in the investigation.

"Judge Berger reminded the convicted coal baron that there was more than money at stake: 'You, Mr. Blankenship, created a culture of noncompliance at Upper Big Branch where your subordinates accepted and, in fact, encouraged unsafe working conditions in order to reach profitability and production targets.'"

Buen hombre

"We often talked about bulls and bull-fighters. I had stopped at the Montoya for several years. We never talked for very long at a time. It was simply the pleasure of discovering what we each felt. Men would come in from distant towns and before they left Pamplona stop and talk for a few minutes with Montoya about bulls. These men were aficionados. Those who were aficionados could always get rooms even when the hotel was full. Montoya introduced me to some of them. They were always very polite at first, and it amused them very much that I should be an American. Somehow it was taken for granted that an American could not have aficion. He might simulate it or confuse it with excitement, but he could not really have it. When they saw that I had aficion, and there was no password, no set questions that could bring it out, rather it was a sort of oral spiritual examination with the questions always a little on the defensive and never apparent, there was this same embarrassed putting the hand on the shoulder, or a 'Buen hombre.' But nearly always there was the actual touching. It seemed as though they wanted to touch you to make it certain.

"Montoya could forgive anything of a bull-fighter who had aficion. He could forgive attacks of nerves, panic, bad unexplainable actions, all sorts of lapses. For one who had aficion he could forgive anything."

- Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises, (1926)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)